For more photos from my trip, check out my tumblr!

Also, if you don’t know what One Piece is, this post will probably hold little significance to you. My apologies! As a One Piece fan, this is a little self-indulgent of me.

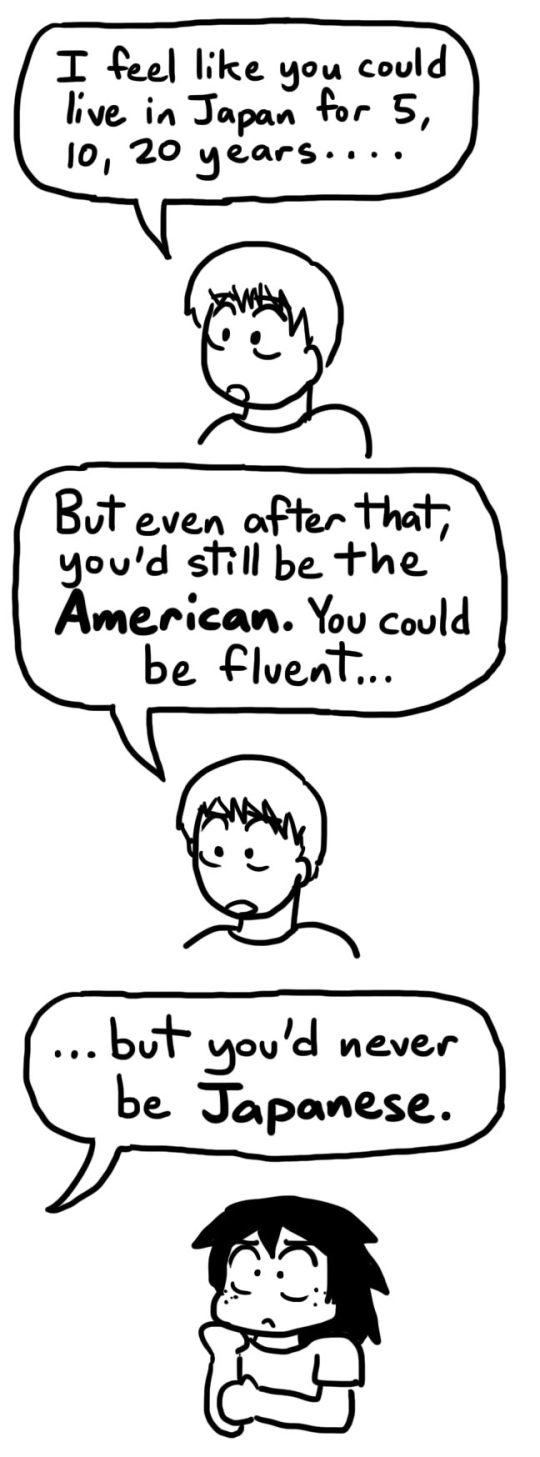

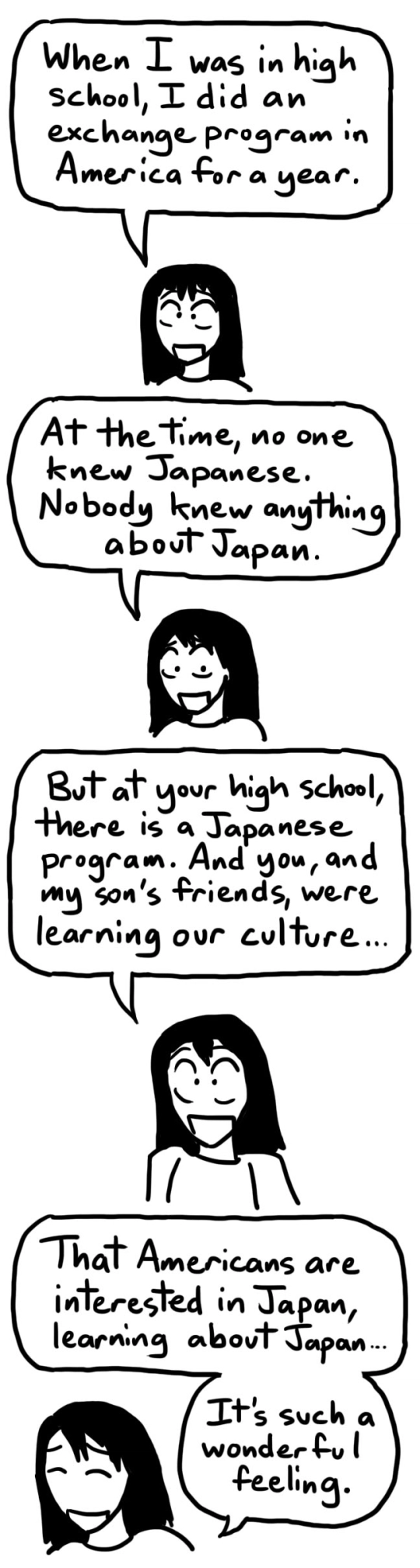

My tutor, who’s been to Japan, once told me this:

I was a little confused. I asked him to elaborate.

One Piece, for those who don’t know, is a manga/anime series that’s been running in Japan for over ten years. It’s about a quirky pirate captain, Monkey D. Luffy, and his quest to find the fabled treasure “One Piece” and become king of the pirates. Throughout his travels, he accumulates a small and equally quirky pirate crew and together they roam the seas. They challenge the elements, other pirates, and even the World Government, weaving a wacky tale of epic adventure.

One Piece also happens to be one of my favorite series, due to its skillful blending of humor and action. It’s kind of well-known in America, too, if you’re into Japanese manga and anime. And I knew it was popular in Japan.

But I was not prepared.

For just how popular it was.

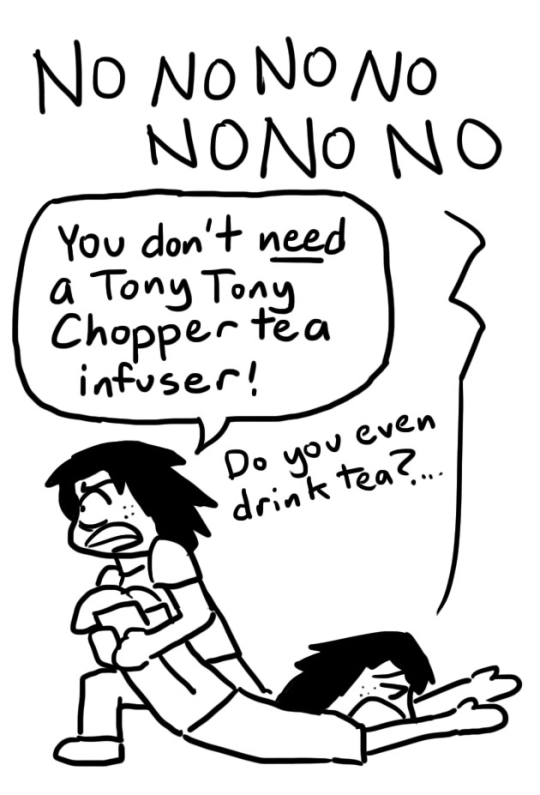

One of the first things I noticed in Japan was just how prevalent One Piece was. One character from One Piece– Tony Tony Chopper– is this little reindeer… thing. He’s cute. Therefore, every single souvenir shop we went to had a whole section devoted to solely Tony Tony Chopper phone charms.

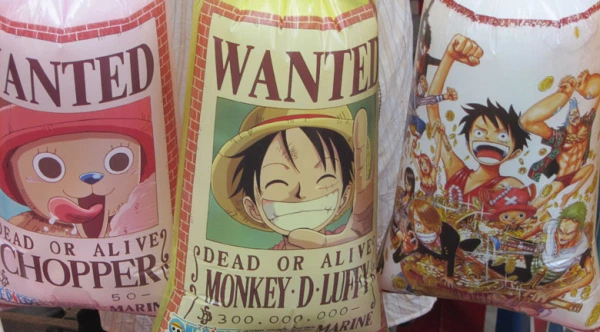

Of course, the phone charms weren’t limited to Chopper alone. There were plenty of the other characters as well.

The merchandise was not limited to phone charms. There were plenty of One Piece socks…

One Piece plushies…

One Piece bags of popcorn…

Even One Piece…bath salts?

A lot of the stores I went to had whole sections devoted to One Piece.

It got even crazier when I realized that a lot of the One Piece souvenirs were created for that specific area. For example, in Tokyo, we’d see phone charms, of, say, Tony Tony Chopper sitting on Tokyo tower.

Or, at Noboribetsu, a hot springs town, we’d see One Piece characters at the hot springs…

Or, at Sapporo Dome, we saw One Piece characters playing soccer:

Japanese souvenirs, as we found out, are a bit different in that way. One Piece wasn’t the only line of characters sold with their own specialized souvenirs. Hello Kitty, for instance, could also be found in most stores:

Another commonly seen character was a bear named Rilakkuma:

There was even a Hokkaido-specific character called Marimokkori, a portmanteau of marimo (a type of green algae ball that grows in Hokkaido’s lakes) and mokkori (a slang term for “erection.”) As you’d expect, some of Marimokkori’s merchandise was a little… weird.

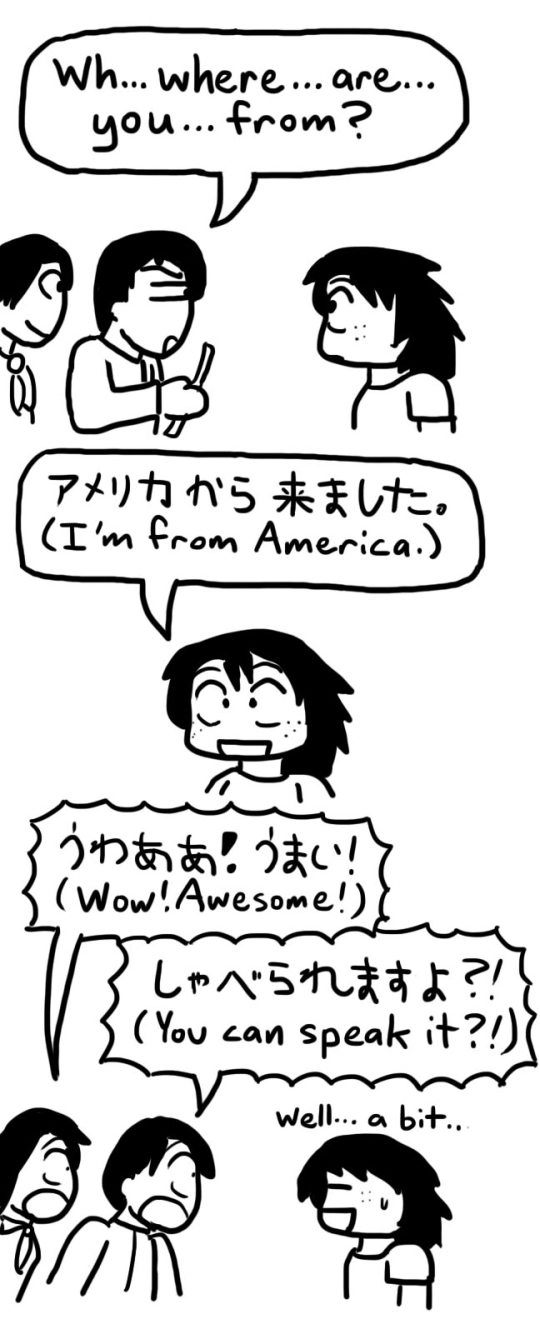

But One Piece was, by far, the most popular. It was everywhere. It pervaded daily life. One of our students had a host brother in elementary school who wore only One Piece t-shirts. I’d often ask people if they watched anime– and the answer would often be:

Occasionally it worked as a conversation starter.

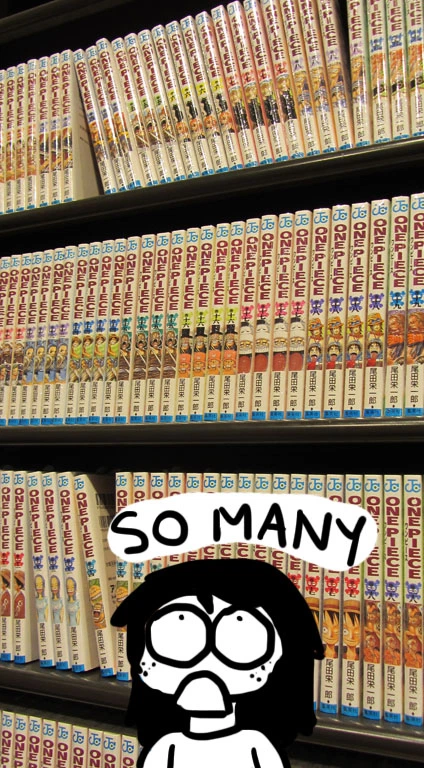

The extent of the popularity of One Piece didn’t hit me, though, until I entered a book store. First, I saw the One Piece section:

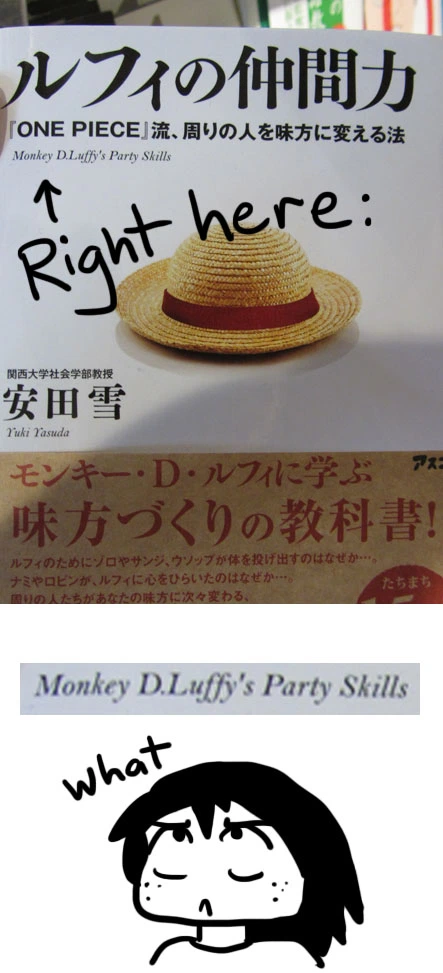

And then I saw a book of One Piece… “party skills?”

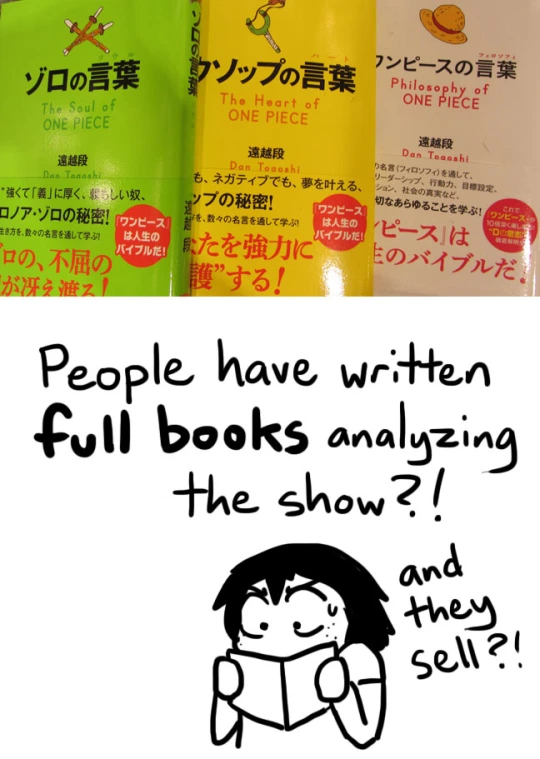

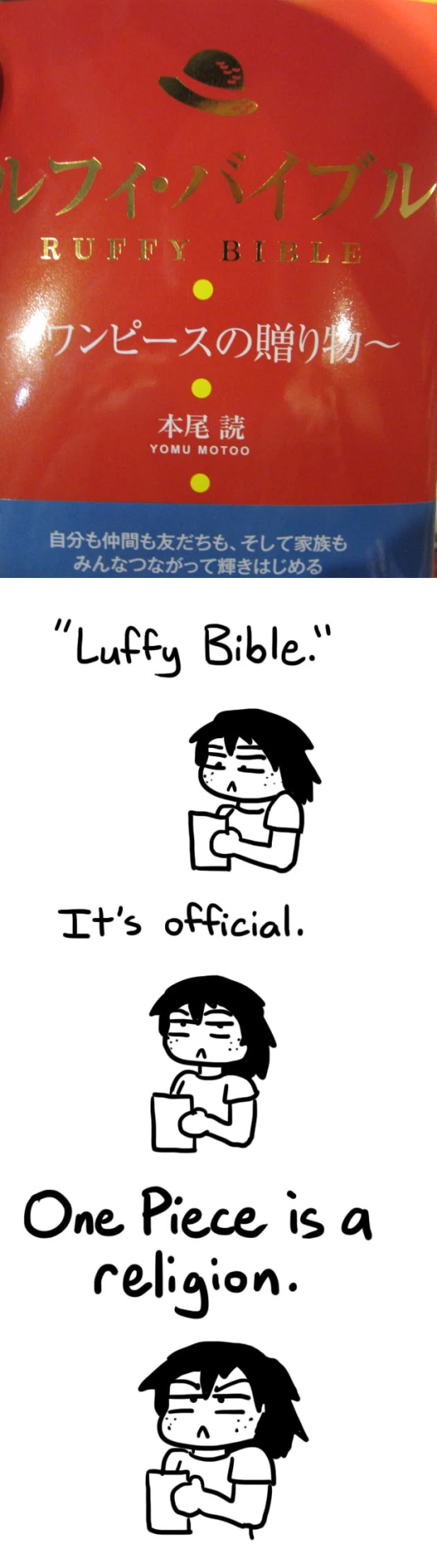

And then I saw this series of books:

And finally, the kicker:

Therefore, my trip to Japan was one of the most trying times of my life. Due to temptation. To my wallet.

So One Piece in Japan was extremely popular to the point where I was shocked. It’s kind of like the Harry Potter of Japan in terms of popularity, except in America there isn’t Harry Potter stuff in all the stores. Really, I’ve never seen anything just be that popular before. Luckily, I managed to practice some self-restraint and not buy everything…